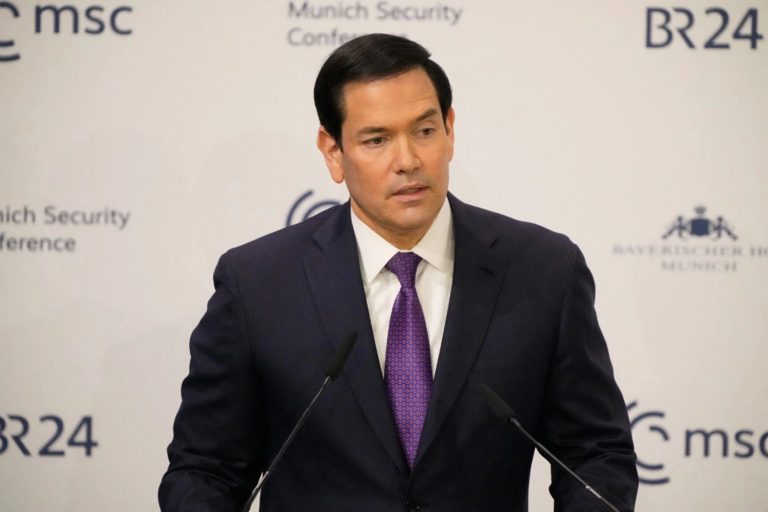

The 62nd Munich Security Conference wrapped up on February 15 with a question that no one on stage could answer: if peace talks on Ukraine collapse, can Europe sustain the war effort on its own? The guiding theme — “Under Destruction” — framed the conference with unusual clarity, but clarity about the problem is not the same as clarity about the solution. Strained ties between the U.S. and Europe took center stage, as Trump’s policies forced both sides to face the consequences of America’s growing belligerence on the world stage. Secretary of State Marco Rubio struck a more conciliatory tone than last year’s pugnacious JD Vance address, but his reassurances came without binding commitments — and with pointed demands that Europe reshape not just its defense budgets but its values.

Rubio told the audience: “We want allies who can defend themselves so that no adversary will ever be tempted to test our collective strength.” Yet his speech made no mention of Russia and criticized Europe’s approach to migration and climate change. He also skipped the “Berlin Format” meeting with European leaders on the war in Ukraine, a signal that Washington wants to lead the peace process bilaterally, not multilaterally. The message was unmistakable: America stays in NATO, but on its own terms and at its own pace.

Money Talks, But Is It Enough?

The spending numbers tell a story of genuine transformation. EU member states’ defense expenditure reached €343 billion in 2024, rising for the tenth consecutive year, and is expected to hit €381 billion in 2025 — an 11% jump and a 63% increase compared to 2020. Defense expenditure rose to 1.9% of EU GDP in 2024, and is expected to reach 2.1% in 2025 — breaching the old NATO benchmark for the first time as a bloc.

Individual countries are moving fast. Germany’s military expenditure surged 28% to $88.5 billion, making it the biggest spender in Central and Western Europe and the fourth largest in the world. Poland’s spending skyrocketed — up 52% in 2023 and another 17% in 2024, bringing the budget to €34 billion at 4.12% of GDP, making it NATO’s top spender by GDP share with plans to reach 4.7% in 2025. Estonia approved a defense development plan allocating over €10 billion for 2026–2029, with priorities including air defense, deep-strike capabilities, and ammunition stocks.

The EU’s Readiness 2030 plan backs this up with institutional muscle. The plan is structured around five key components designed to mobilize both public and private resources, with an estimated potential to unlock nearly €800 billion for European security over the coming years. A €150 billion loan instrument — Security Action for Europe (SAFE) — will help countries invest in missile defense, drones, and cybersecurity. The European Defence Industry Programme adds €1.5 billion in grants for 2025-2027 to boost production capacity.

The shift goes beyond budgets. Old “just-in-time” procurement models are giving way to long-term contracts, larger ammunition stockpiles, and more resilient supply chains. At NATO’s Hague summit in June 2025, allies agreed on a new defense investment commitment of 5% of GDP by 2035. On the eastern flank, deployments have grown from battalion-sized units to brigade-level formations. With Finland and Sweden now inside the alliance, attention has expanded to the Arctic and critical maritime infrastructure.

The Ukraine Test

All this rearmament means little if it cannot be translated into sustained support for Kyiv. Russia is suffering staggering losses — roughly 65,000 soldiers in the last two months alone, according to NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte. Rutte insisted NATO would “win every fight with Russia if they attack us now” but stressed the need to ensure the same holds true in two, four, or six years.

Zelensky told the conference that Ukraine “needs a date” for EU accession and aims to be technically ready by 2027. He warned that without a timeline, Russia would attempt to block Ukraine’s path — directly or through other countries. He also said he felt “a little bit” of pressure from Trump, noting that American negotiators too often discuss concessions “only in the context of Ukraine, not Russia.”

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called for a new security strategy that could bring a “mutual defense clause to life,” while British Prime Minister Keir Starmer said Europe must build “hard power” and be ready to fight if necessary. The UK announced it will deploy its carrier strike group to the North Atlantic this year alongside U.S. and Canadian forces.

But the gap between rhetoric and operational readiness remains real. Despite sustained spending increases, EU members continue to lag behind other major powers — the United States spent €845 billion in 2024, nearly two and a half times the combined EU total. Although EU countries collectively possess more battle tanks, artillery systems, and infantry fighting vehicles than their rivals, their capabilities are fragmented across different operating systems, making them less effective than the numbers suggest.

What Munich revealed is a Europe that has genuinely changed direction — spending more, planning longer, thinking harder about war. But it also revealed a continent that has not yet told Washington, “We’ll take it from here.” The psychological shift may be the most important development of all. Converting that mindset into a war-sustaining capability, however, requires something European leaders have historically struggled to deliver: speed, unity, and the political will to match their own promises.

Original analysis inspired by Anna Magdalena Wielopolska from Kyiv Post. Additional research and verification conducted through multiple sources.