Recent U.S. military operations near Venezuela have tested Beijing’s commitment to its “all-weather strategic partnership” with Caracas, revealing patterns of rhetorical support, sustained economic engagement, and carefully calibrated military cooperation—but notably absent security guarantees or significant new financial commitments. This case study illuminates China’s approach to partnerships facing Western pressure and the practical limits of solidarity declarations.

Diplomatic Response and Strategic Positioning

Following September’s Operation Southern Spear—which deployed approximately 15,000 U.S. troops and the USS Gerald R. Ford carrier task group to the Caribbean region—Chinese Foreign Ministry officials articulated strong positions defending Venezuelan sovereignty. At an October UN Security Council emergency meeting, Chinese Ambassador Fu Cong characterized U.S. deployments as serious sovereignty infringements violating international law and threatening regional peace.

Subsequent Foreign Ministry statements emphasized opposition to “external forces interfering in Venezuela’s internal affairs under any pretext,” formulations repeated across multiple briefings to establish Beijing’s diplomatic position. Senior spokesperson Mao Ning affirmed that China-Venezuela cooperation remains “not aimed at third parties and not affected by third party interference,” sidestepping allegations about Chinese weapons supplies while framing bilateral ties as sovereign state cooperation.

Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s December conversation with Venezuelan counterpart Yván Gil invoked Beijing’s standard formula for defending partnerships facing Western criticism: opposing “unilateral bullying” while supporting nations’ rights to self-defense and dignity. This language positions China as defender of Latin American autonomy against external interference while deliberately avoiding specification of concrete security commitments or consequences.

The All-Weather Partnership Framework

China and Venezuela established their “all-weather strategic partnership” status in 2023. Within China’s extensive diplomatic partnership taxonomy, “all-weather” carries particular weight, implying expectations of maintaining very close relations with countries Beijing perceives as stable long-term partners. This classification places Venezuela alongside Pakistan, Belarus, Ethiopia, Uzbekistan, and Hungary in China’s partnership hierarchy.

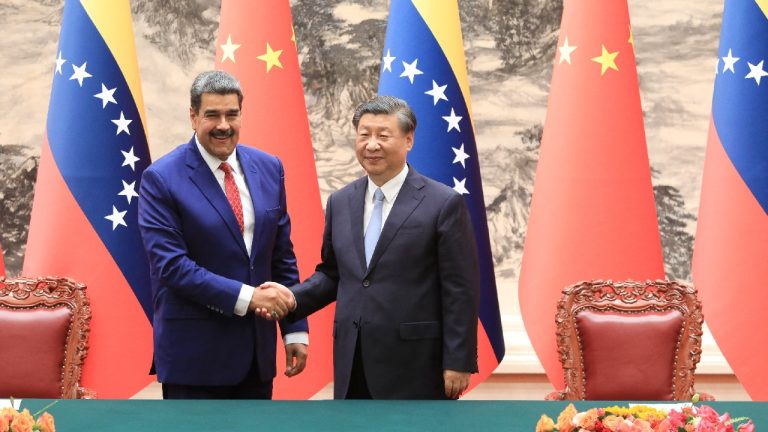

During May 2025 Moscow meetings, General Secretary Xi Jinping told President Maduro that China would “continue to firmly support Venezuela in safeguarding national sovereignty, national dignity, and social stability” while emphasizing willingness to “strengthen exchanges on governance experience.” These formulations reflect Beijing’s broader Global South solidarity narrative against Western hegemony.

Chinese Ambassador to Venezuela Lan Hu explicitly linked contemporary resistance to U.S. pressure with World War II commemorations, praising Venezuela’s historical resilience before emphasizing both countries must “resolutely oppose hegemony and unilateralism.” At December press conferences, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian invoked the 2014 Proclamation of Latin America and the Caribbean as Zone of Peace—signed by 33 states committing to peaceful dispute resolution—to challenge U.S. military presence in the Western hemisphere.

Energy and Economic Foundations

Venezuela’s strategic value to China rests primarily on energy security. According to shipping data, Venezuela exported approximately 921,000 barrels per day in November 2025, with roughly 746,000 barrels (80%) destined for China. Even after U.S. seizure of Venezuelan oil tankers in December, Chinese imports were predicted to reach 600,000 barrels daily—significantly increased from 268,000 barrels per day in mid-2024.

Chinese state-owned enterprises maintain direct operational stakes in Venezuelan energy infrastructure. China National Petroleum Corporation holds shares in four joint ventures producing heavy crude from Orinoco Belt, while Sinopec operates refineries processing Venezuelan oil for Asian markets. This follows “loans-for-oil” structures established during Hugo Chávez’s presidency.

Between 2007-2025, China provided Venezuela over $60 billion in development loans typically secured against future oil shipments at predetermined prices. While new lending largely ceased due to Venezuela’s economic collapse and repayment difficulties, existing debt obligations—reportedly exceeding $20 billion—continue structuring bilateral trade. Recently, China Concord Resources Corp signed a 20-year production sharing contract including $1 billion investments, though beyond petroleum, Chinese engagement focuses largely on mining and infrastructure.

Military Cooperation and Equipment Sales

Chinese officials deny providing offensive weapons, but evidence suggests growing defense relationships. Recent meetings between Ambassador Lan Hu and Venezuelan Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino López affirmed aerospace cooperation and expressed hopes to “strengthen exchanges and deepen cooperation” in defense sectors.

Chinese equipment alongside Russian materiel increasingly underpins Venezuelan military capabilities. Venezuela’s defense posture now relies on Russian-made Su-30MK2 fighters, Chinese-made VN-18 infantry fighting vehicles, Type 05 amphibious assault vehicles, and SH-16A howitzers. Multiple Chinese media outlets reported Venezuela negotiating to purchase 20 J-10CE fighters—which would represent Caracas’s first Chinese combat aircraft acquisition.

Venezuela has historically purchased Chinese military equipment including K-8 trainers, Y-8 transport aircraft, and JY-27A air defense radars acquired in 2019. These systems, while not China’s most advanced capabilities, provide Venezuela options unavailable from traditional suppliers facing Western sanctions.

The People’s Liberation Army Navy established Caribbean presence in response to American deployments. In August 2025, the Type 815A electronic reconnaissance ship Liaowang appeared in international waters near Venezuela’s Paria Gulf, operating in overlapping zones with U.S. naval forces. Chinese military commentators cited PLA deterrence doctrine, describing the deployment as demonstrating “asymmetric deterrence” capabilities. While the vessel eventually departed without incident, its presence signaled China’s capacity to monitor U.S. operations in the Western hemisphere.

In November, hospital ship Silk Road Ark made its first unannounced port call to Nicaragua—Venezuela’s close ally—as part of “Harmonious Mission 2025” deployment. State media framed the voyage as contribution to “community of common destiny for mankind,” though the timing and location suggested low-level deterrence signaling.

December Policy Paper and Regional Strategy

China’s December 10 release of its third “Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean”—following 2008 and 2016 versions—frames the region as core Global South component. The document emphasizes sovereignty, non-interference, opposition to unilateral coercion, and rejection of bloc confrontation as engagement foundations.

The policy paper signals intent to deepen military ties through regular engagement and institutionalized dialogue, including increased defense leader interactions, naval visits, delegations, and closer cooperation in training, professional education, and peacekeeping operations. Beyond traditional military links, it encourages cooperation on humanitarian assistance, counterterrorism, and non-traditional security challenges, alongside expanded arms trade and defense industrial collaboration.

Beijing presents multilateral forums as key platforms, pledging to continue hosting regional defense dialogues and encouraging Latin American participation in China-led security forums. The document praises countries for “strictly observing the One China Principle” and “opposing any form of Taiwan independence,” linking regional engagement to core Chinese interests.

Limits of All-Weather Support

The current crisis reveals practical limits of Chinese support. Chinese loans to Venezuela have effectively ceased since 2020, with existing exposure already considered problematic. Trump administration blockades of sanctioned oil tankers present additional complications for China-Venezuela oil trade.

Consistent with all Chinese partnerships, no mutual defense obligations exist. Foreign Ministry spokespersons have consistently demurred on military support questions. When questioned about alleged weapons supplies, Mao Ning vaguely referenced combating transnational crime before noting U.S. military force usage for such goals—carefully avoiding security commitment specifics.

Chinese media coverage has been notably restrained compared to Beijing’s responses to perceived U.S. provocations elsewhere. While Foreign Ministry spokespersons issue routine sovereignty defense statements, state media outlets have avoided inflammatory rhetoric that might complicate U.S.-China relations. Treatment contrasts between Venezuela and Asian disputes suggest Beijing views Venezuelan support as ultimately secondary to mitigating tensions with Washington.

Broader Implications for Chinese Partnership Models

China’s Venezuela response illuminates its partnership model characteristics when partners face existential pressures. Beijing maintains access to strategic resources (Venezuelan oil), preserves its reputation as reliable partner to Global South states, and demonstrates capacity to project presence in Western hemisphere—all while avoiding commitments that could jeopardize U.S.-China relations or expose Chinese assets to significant risks.

This calculated approach—vocal diplomatic support, continued economic engagement, calibrated military sales, but no security guarantees—reflects China’s prioritization of flexibility over solidarity when partnerships encounter major power confrontation. “All-weather” partnerships offer rhetorical support and sustained commercial relationships but not defense commitments comparable to traditional military alliances.

For Venezuela, this means Chinese support provides diplomatic cover, energy market access, and military equipment options unavailable from Western sources. However, it does not guarantee intervention if U.S. pressure intensifies or regime stability deteriorates fundamentally. For other countries considering deepening China relationships, Venezuela’s experience suggests limits to partnership benefits during crises.

For the United States, China’s measured response indicates reluctance to escalate Caribbean tensions into broader U.S.-China confrontation, suggesting space for American action without triggering Chinese military intervention. However, continued Chinese economic engagement and military equipment sales complicate U.S. efforts to pressure Venezuela through isolation strategies.

The Venezuela case tests whether China’s partnership model—emphasizing economic statecraft, diplomatic solidarity, and strategic ambiguity regarding security commitments—can sustain relationships when partners face major power pressure. Evidence suggests this model provides meaningful but limited support, prioritizing Chinese interests in maintaining stable great power relations over comprehensive partnership obligations.

Original analysis inspired by Dennis Yang from Jamestown Foundation. Additional research and verification conducted through multiple sources.